It is the spring of 1922 and my father stands in front of the old red brick schoolhouse. He is clad in dark trousers, corduroy shirt, and sport jacket. This day could have been his graduation, a fine spring day in May. The morels must have been pushing their way up through the pungent floor of the North Woods. But I know this is no graduation day. Mother always made that abundantly clear that you never finished school. “Just remember, John Dee,” she would tell me, “any brains you received came from my side of the family, not his.”

But I refuse to believe that. Not now, at least, holding your picture out at arm’s length like this in this cold March wind. I will do exactly as you asked. I will bury the past for the future. I spear my shovel into the frozen earth, but your picture continues to captivate me. I take a closer look. There is something casual, almost cavalier in your manner on that day, the way your right foot extends out and the jacket thrown back with both hands resting on your hips. You look . . . Gatsby esque, wearing your porkpie—except, well, that is no Daisy on your left arm either.

“John. Put your hat on Ailda,” Hoy says. He is the unseen one standing back a few yards, the eye of the camera. You grin and take the porkpie off and plop it on Ailda’s head. She wears her hair fashionably short. Your hair is dark and combed back, giving you a baby-face, loose-jointed look.

Hoy comes over and adjusts the hat to a rakish angle. A breeze passes through the maples and makes the leaves rattle. I can tell by the way that your shadows have merged into a short, inverted V that it is just past noon. The moment is set forever, frozen.

But your left foot reveals something else. You are leaning back slightly on it, striking the pose, causing the pant cuff to move up a little, exposing the thick, heavy-laced work boots that run high up your foot, past your ankle. The toes are worn and need polish. They form the left point of the shadow that points north, where the plot of land lay.

It is your right hand that interests me, so nonchalant next to your pant’s pocket with your thumb hooked in. Only a bird’s eye would have noticed it. At first I thought it a meaningless gesture, or possibly you were giving the okay sign to the camera, until I got out the magnifying glass. Your forefinger encircles it, a smooth dark stone, and the same one that now sits on the mantel piece in the living room of The Stone House.

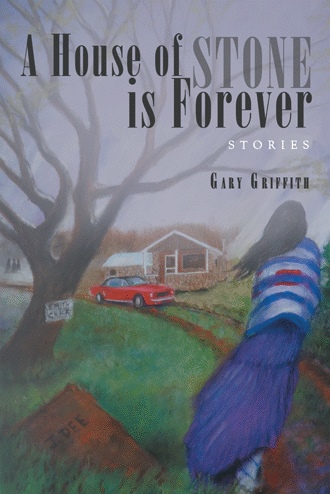

Your shadow points north, toward the site a short distance away, where across the field, up the knoll and beneath the box elder tree, ten years after, you would one day build your house of stone. You and C.P. are walking up the path that cuts through the apple trees, tall grass, and the hollyhocks. C.P. is pushing your old, rusted out wheelbarrow, while you stroll along beside him. Neither of you are in any particular hurry. The apple blossoms are out and bees are droning. The wheelbarrow is filled with palm-sized stones that are shaped like prehistoric eggs. “We’ll use them later on for the porch,” you would tell C.P. “But for now they’ll be markers.” C.P. labors to keep the load even because he was the first born and the eldest and therefore all responsibility will lie with him to watch over me and all of the others, when we entered the world: Marie, little Jane, Andrew, Alfie , and of course me.

C.P. leans into the load of stones and looks at his arms, searching for veins, but there ain’t none, not now, least ways. Pa strolls alongside in that long-legged easy manner of his, swaggering slightly in the rhythm of things, one hand knuckle-deep in his britches, the other dragging the shovel behind. He looks at the stones as if they ain’t really stones but something else, like buried treasure or something. He says to C.P., “Stack a pile over yonder, C.P.,” pointing toward the northeast corner. And C.P. runs back and forth like a jackrabbit until every last one of ‘em are in place, and the pyramid is built just like Pa wanted, shaped on three sides with one on top. Then he sends C.P. for another and another and another, until everything is laid out.

Just then the courthouse bell begins sounding. Twelve times it rings in those clear tones. You can almost see the belfry, being up high and behind things like this, on the knoll that Ma picked out. The only thing keeping it from sight is the maples, thick and green and moving slightly in the summer air. There are trees beneath them layer after layer, running down toward the valley, where town is.