Posadas

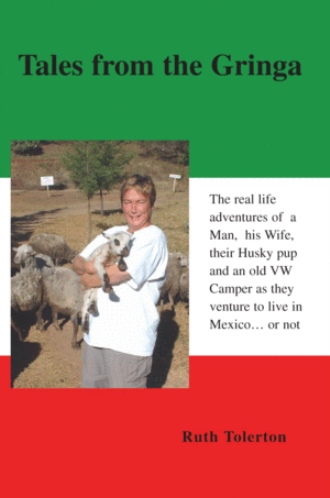

Mid December found the Gringa, husband and dog still living in San Patricio de Melaque. This was familiar stomping ground as they had holidayed in this town of 5,000 frequently over the last ten years. Melaque is situated at one end of the Bahia de Navidad, with the slightly more trendy Barra de Navidad located at the opposite end of the three mile beach. Melaque is a town devoted largely to Guadahajaran and other Mexican tourists, while Barra holds appeal for funky Norte Americanos. Both have an almost cult following among Canadians and Americans and although the “secret” was closely guarded, it seemed that the number of non-Mexican license plates was threatening to outnumber locals.

Around the pool at their complex the population consisted mainly of the Canadian and American snowbirds taking refuge for two weeks to three months, although the longer stays were the more common. All were quite accustomed to the weekender buses from Guadalajara which disgorged circus levels of Mexicans anxious to party, without sleep, for their short vacations. As the buses arrived, so the local gringos retreated to their rooms – the beaches would be noisy and polluted for the weekend’s duration and the pool waters took on a murkiness that discouraged cooling off.

It was the consensus of Melaquans and snowbirds alike that of all the creatures under the sun, none was more slovenly than the Mexican tourist. Their love of holidaying and partying with family totally obliterated their normally cleanly habits – litter was dropped where convenient to the user (often within two feet of a rubbish container), broken glass was left to sparkle on the beach sand, the pool waters were murky because… And the locals, while realizing that extra work hours would follow the departures, nonetheless actively encouraged this branch of tourism. Room rates were charged on a per person basis and increased each weekend or holiday period a base rate of 800 pesos plus 150 pesos per person per night. The demand for rooms was high and the prices undisputed so these Mexican tourists were paying for the otherwise slow economy. The Gringa and her husband occupied a one-bedroom apartment with rent set at 4,500 pesos per month (roughly $450 US). Next door was a two-bedroom apartment. One morning while breakfasting on the balcony, they counted twenty-two Mexicans of various ages disappearing into the room for a weekend’s stay. Their luggage consisted of the omnipresent vinyl shopping bags, blown up beach toys, bags of farina and assorted grocery bags clinking with promise of good times. The innkeeper was collecting almost 4,000 pesos for the suite per night. Apparently they meant to sleep in shifts, if at all.

Now at mid December, the holiday season was about to swing into high gear with this holiday second in importance only to Easter in Mexican festivities. The loaded down tourist buses would start arriving in earnest in a few days time, and the inn keeper was forcing our Gringa, husband and dog out of their apartment until further notice. Monthly rent could not compare with the holiday rents paid by Mexicans over the next three weeks. She wouldn’t confirm the availability of apartments in the New Year but promised to constantly “checky checky” and keep in mind that they would be returning mid-January.

The Gringa and her husband had decided that they would travel to the mountains – sure to be deserted as all the mountain people flocked to the beaches. They had neither reservations, nor specific destinations other than heading to the State of Michoacan – touted highly by their German American neighbour as one of the more beautiful places in Mexico.

Before their travels began again in earnest, there was time to sample the festivities. Melaque loved a good fiesta and practically any occasion was sufficient to loudly rejoice. So far in their six week stay there had been several parades for the Revolution Day. There had been at least two crownings of very junior queens as the numerous nursery schools and kindergartens took to the streets in parade. The pint size youngsters were arrayed in their very shiniest tiaras, fancy dresses and garlands, with the to-be queens arrayed decorously on the hoods of new models cars.

The Christmas season was celebrated in almost every town and village with Posadas – a triumphal procession re-enacting the Blessed Virgin and Joseph seeking room at the inn. Having spent many hours seeking her own room at the inn, though happily not in a blessed state, the Gringa was eager to witness the Mexican version. Fed by street rumour of a posada that night, she set off just as the sun was setting to find the parade in their suburb of Obregon, home to the working poor.

Unusually the evening promised rain, and the streets were strangely deserted in advent of a Mexican parade. Asking passers by of the location of the posada, she was given typically vague and conflicting directions. Certainly there were no crowds lining the streets to cheer on the participants in their quest. Finally she found herself outside the open doors of the local church. Catechism class was in full swing with the congregation of mostly children answering in one voice. Having assured herself that this must be the starting point for the posada, the Gringa popped open a can of pop and lit up a cigarillo to wait. She was perched on a nearby wall and had a good view of the proceedings through the wide open doors. The supervising adults motioned for her to join in the congregation but being non-Catholic and mid cigar, she smiled and declined. It was a very progressive church with its doors open to all – several of the neighbourhood dogs wandered freely through the chanting children.

After a lengthy time, there was much stir and excitement within the church. The children were mustered into formation and all handed lit candles. The wealthier of the children were easily identified – they had on good clothes with the boys wearing ties and the girl’s fancy confirmation dresses (though those fortunate enough for lace concoctions were often paraded at the Sunday night ritual walks around the town square). Glow sticks in addition to the traditional candles evidenced further proof of wealth. Some of their poorer compatriots were in clean pants long outgrown and barefoot.

The Gringa moved down the block and set in place with her digital camera to record the ritual. She was quite stunned and amused to see that reality had a place in Mexican life – the lead Mary was obviously quite expectant, though the round belly was quite at odds with her nine year old face and figure. One had to wonder how prophetic that belly was in this youngster’s life and how few years would pass before she would be parading the real thing in the village square.

The children sang hymns as they walked along, candles carefully shielded against the raindrops. Oddly, no one came out of his or her houses to salute their march and so they were quite delighted with presence of the Gringa, and more particularly her camera. Mary and Joseph remained serious while the rest of the villagers jumped about and aped for the camera.